I've taken Mike Shedlock a/k/a Mish to task on a couple of items lately. But one of his graphs tells a very interesting and timely story that is worth a little more in-depth discussion.

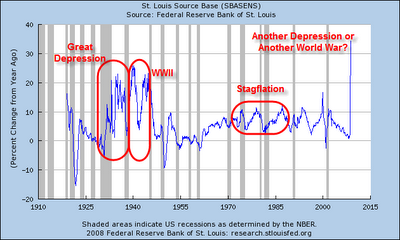

Most people who have read about the Great Depression understand that part of what happened is that the money supply (M1 and M2) contracted sharply and that there is a school of thought that this was a prime driver of the Depression. But then there's the anomaly shown in this graph:

As I will discuss below, the two spikes in the monetary base - in December 1930 and October 2008 - have a lot in common.

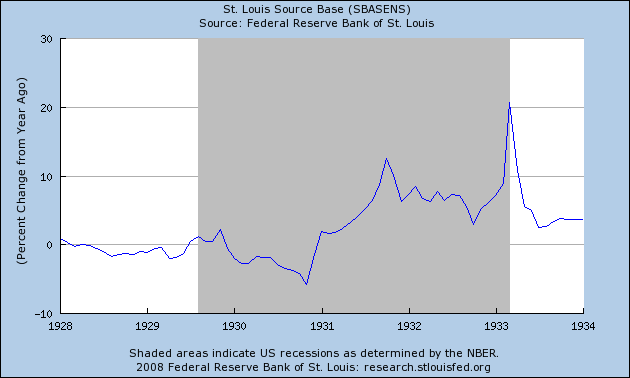

As can plainly be seen, about midway through the Depression the monetary base expanded dramatically. Here is a closer look:

So, what happened in December 1930 to cause the explosion in the monetary base and why didn't it end the Drepression? Therein lies a story of importance for our current Crisis.

As I described in my diary, 1930, the Great Depression really started as an "autonomous consumer decline" before there was a substantial contraction of money supply, or trade wars, or bank runs. Those all started in 1930, the bank runs outside of a couple of farm areas only in the last two months of 1930. This run on the banks at the end of the year, as it turns out, is crucial to explaining the expansion of the monetary base. There was a bristling exchange between Prof. Paul Krugman and Prof. Anna Schwartz on this very issue last year.

Here's Krugman:

In interpreting the origins of the Depression, the distinction between the monetary base (currency plus bank reserves), which the Fed controls directly, and the money supply (currency plus bank deposits) is crucial. The monetary base went up during the early years of the Great Depression... But the money supply fell sharply... This divergence mainly reflected the fallout from the wave of bank failures in 1930–1931: as the public lost faith in banks, people began holding their wealth in cash rather than bank deposits, and those banks that survived began keeping large quantities of cash on hand rather than lending it out, to avert the danger of a bank run. The result was much less lending, and hence much less spending, than there would have been if the public had continued to deposit cash into banks, and banks had continued to lend deposits out to businesses.

....

Friedman and Schwartz didn't say that. What they said instead was that the Fed could have prevented the fall in the money supply, in particular by riding to the rescue of the failing banks during the crisis of 1930–1931. If the Fed had rushed to lend money to banks in trouble, the wave of bank failures might have been prevented, which in turn might have avoided both the public's decision to hold cash rather than bank deposits, and the preference of the surviving banks for stashing deposits in their vaults rather than lending the funds out. And this, in turn, might have staved off the worst of the Depression.

And here is Schwartz's reply:

Krugman claims that Friedman engaged in crude assertion by stating that the Federal Reserve "permitted a sharp reduction in the monetary base." In fact, the monetary base declined over 5 percent from April 1928 to October 1930, certainly a sharp reduction; details are in pages 290, 340–342, and 803 of the Monetary History... The 1930–1933 increase in the monetary base did not reflect official ease, as Krugman implies, but the general public's flight into currency in response to their distrust of banks. Only the currency component of the base rose; the bank reserves component declined (pp. 739–740).

....

[In] 1973 Friedman [said]:

Just as banks all around the country were closing, the Fed raised the discount rate; that's the rate they charge for loans to banks. Bank failures consequently increased spectacularly. We might have had an economic downturn in the thirties anyway, but in the absence of the Federal Reserve System—with its enormous power to make a bad situation worse—it wouldn't have been anything like the scale we experienced.

Friedman clearly characterized the problem as Federal Reserve failure to support commercial banks.

In other words, in response to the first bank run at the end of 1930, the public started to hoard cash. Therefore Federal Reserve had to constantly replenish the actual cash in circulation, thereby increasing the monetary base dramatically.

Mish is making the argument that essentially the same thing is happening now: banks are hoarding cash and refusing to lend.

While I disagree with the "refusing to lend" part, the rest of the analysis has great merit. Certainly we haven't had a traditional "run on the banks" in 2008, but I believe we have had the 21st century equivalent: a run on hedge funds. In October alone, according to some stories, $100 billion was taken out of hedge funds! Readers may recall that several money market funds "broke a buck" and closed in September, and investors began to panic about those as well, until their funds were guaranteed by a "MMDIC" insurance fund set up by the Federal government. It is most likely this panic that was relayed to Congress by Bernanke in asking for the immediate injection of $700 billion into the banking system at that time.

Mindful of Friedman's analysis of the Great Depression, Bernanke was not about to let the "banks" fail as in December 1930. Fed funds was allowed, effectively, to fall to 0%, and banks were reliquified -- or made solvent, depending on your point of view -- with a massive increase in the monetary base.

In both cases, the surge in the monetary base was a direct reaction to a "run on the banks" during a solvency crisis of the financial system. From the end of 1930 to mid-1933 the public hoarded cash, and the Great Depression wound on. If Mish is correct, a similar thing is happening now. If, on the other hand, banks are gradually increasing their lending, and M1 and M2 continue to increase as they have for the last 4-6 months, there may yet be a respite by summer of next year.

Comments

I thought it was contracted

I thought the fed during that time tightened the money supply as well as lending during 1930-1933.

M1 and M2 contracted into 1933

but as shown above, from the middle of the depression on, the monetary base expanded substantially.

Iirc, there was no concept of "M1" or "M2" at the time, so the Fed had no way of keeping track of it, wherease they did have data for and kept track of the monetary base.

M3 & graph

I was wondering about M3 (did they divide that at all in the 1930's?)

But, in your graph, you have the great depression circled, but to me the real woe was from 1929-1934 and there is looks like a contraction, with a response after the fact of increasing it.

It would be nice to zero in on that time period.

I think things fundamentally improved until the 1937 period but didn't they try to reign in federal spending due to the budget deficit at that time?

I gotta do some research

there's something nagging at the back of my skull at this point- ratios of M1 to M2 to M3 to GDP. Almost as "if real money ain't there, borrow it" seems to be a precursor to all of this.

Not sure though.

-------------------------------------

Maximum jobs, not maximum profits.

And with Madoff's failure

That's what I like about this economics site above all others- the predictions match reality. With the arrest of Bernard L Madoff and the collapse of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities reported yesterday, we have sudden insight into the main problem of Hedge Funds- the flat trading commission, people paid according to market volume rather than according to whether or not the trade made anybody any money.

The way I see it, next summer's so-called respite at this rate (along with the obvious hoarding of cash going on with 4-week T-Bills hitting 0%) will be just a respite on paper- accompanied with a food famine.

-------------------------------------

Maximum jobs, not maximum profits.

Great article, and if I may add

to that part about a run on mutual funds. It should be noted, that most of these funds have "closed the window" per say on redemptions. They can still get their money out, but as per agreement when they signed on, when the window is closed the time limit is essentially extended. The Madoff affair started with foreign investors, being more skeptical of the returns versus those here in the US, started demanding their money. He couldn't come up with it, as per a ponzi scheme, the funds had already been distributed to one of the earlier investors.

Also

could the lack of lending towards investment/trading and M&A be regarded as having the same effect as the Fed raising interest rates? I know it's a stretch, with one being a reserve action, yet aren't the results similar?

Lastly,

could you put up a chart that overlays growth (or recess) in inflation y/yr with that of M1 & M2?

consumer credit + consumer spending == hording

Right now there's a huge pull pack in consumer spending and a corresponding tightening of credit by the high interest sector of the consumer credit market. That's equating to the "run on the banks" seen in the 1930s. Today, America is a debtor nation and depositors have FDIC to insure that their deposits are safe and the FedTreasury seems all too willing to throw as much at the intrabank lending problem as will be required. So, looking back at how the great depression went down is the ultimate "driving with your rear-view mirror" exercise.

The vast majority of America lives paycheck to paycheck and even those that have a safety fund probably can't last much longer than 8 to 12 months (those that don't will use their credit cards with exactly the same eye that they appraised the subprime real estate proposition... can't get blood from a stone, so why not). I'd be paying *very* close attention to the consumer credit market. It's the new heart beat of mainstreet America. After that, unemployment and tax revenues.

We're getting back to fundamentals after years of castles in the sky...