New research reveals how work permits reduce child labor violations

One year ago, EPI published a blog post summarizing research on the effectiveness of youth work permits in reducing child labor violations. Updated findings by the study’s authors reveal the mechanisms and features of work permits that make them so effective.

Amid increased child labor violations, youth work permit systems have been under attack in some statesIn recent years, child labor violations have been on the rise across the country. At the same time, lawmakers in many states have proposed bills to reverse long-standing state child labor standards that prohibit employers from exposing youth under 18 to hazardous jobs or overly long work hours that interfere with their health and well-being. Youth work permits—which many states have historically required—have been a repeated target of this coordinated, industry-backed campaign to weaken child labor laws. Such permits typically require employers to outline the potential hours and work duties for a minor worker, as well as parental approval and verification that the minor is attending school.

Since 2021, lawmakers in at least nine states have proposed weakening or eliminating youth work permit systems, and four have enacted such legislation (Alabama, Arkansas, Iowa, and West Virginia). Most recently, in 2025, Alaska Governor Mike Dunleavy encouraged the legislature to pass a bill that would have eliminated the requirement that minors receive individual authorization to work (and replaced it with a general authorization for employers to hire minors). And in West Virginia, lawmakers successfully eliminated youth work permits for 14- and 15-year-olds and replaced them with age certificates following a two-year push by the right-wing think tank Foundation for Government Accountability (FGA). FGA has played a leading role in efforts to eliminate youth work permits in Arkansas, Iowa, Missouri, and Wisconsin.

New research explains how and why youth work permits are so effectiveProponents of eliminating youth work permits have often argued that work permits are not necessary, are overly burdensome for employers, or that they infringe on parents’ right to decide whether, where, and how long their child should work. In reality, work permits are a proven, effective policy for ensuring that young teens can enter the workforce safely by making sure employers are aware of child labor laws and that parents are fully informed about the conditions of a proposed job.

A year ago, we reported on research providing new quantitative evidence that work permits help prevent federal child labor violations. Using comprehensive data from the U.S. Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division from 2008 to 2020, researchers at the University of Maryland and Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, found that states requiring employment certificates saw 13.3% fewer violation cases and 31.8% fewer minors involved in these violations.1 States with work permits also saw 34.9% lower civil penalties per minor, indicating reduced severity of violations that do occur.

New findings from the same research team now reveal two key mechanisms that explain how work permits provide this protection: 1) work permits create a documentary paper trail that increases employers’ accountability and aids government enforcers, and 2) work permits improve compliance with state and federal standards by increasing employers’ awareness of child labor laws. According to the new analysis, requiring verification of parental consent for a minor to work and providing education to employers about hours restrictions are the main features that make work permits effective. State lawmakers can use the new findings to strengthen and modernize their youth work permit systems, using strategies proven to reduce violations and protect youth well-being.

Work permits create legal accountability and enable effective enforcementResearchers found that work permits enable more effective enforcement of child labor standards by creating a record that employers were informed of child labor standards, therefore making it harder for employers to claim ignorance if violations occur. By analyzing publicly available federal court records, researchers found that in states with work permit mandates, 91% of child labor cases were classified as “willful” or “repeated” violations. These more serious classifications carry higher penalties. In contrast, only 33% of cases in states without work permit mandates received these classifications.

This finding implies that when employers hiring teens must complete a work permit that documents the minor’s age, obtains parental consent, and acknowledges legal requirements, they are made aware of child labor standards and can fully comply with state and federal laws. Work permits also enhance the investigatory capacity of federal enforcement agencies by providing basic documentation about youth employment that investigators can scrutinize when they suspect violations of federal law, as well as bolstering their ability to take effective action if an employer violates the law despite having been informed.

Work permits enhance awareness of specific child labor standardsSecond, researchers found that work permits enhance awareness and monitoring of employers’ compliance with federal and state laws—but only for standards that are explicitly mentioned in the permitting process. Analyzing all relevant Department of Labor news releases detailing specific violations (118 in total) from 2020 through 2025, researchers found that work permits reduce precisely the types of violations that the permit forms explicitly warn employers are prohibited under federal law. As Figure A highlights, states with work permits showed: 1) fewer hours violations—minors working beyond federally permitted hours (e.g., federal law limits 14–15 year-olds to 18 hours per week during school weeks); 2) fewer age-limit violations—employment of children below minimum working age (typically 14 for nonagricultural work); and 3) fewer recordkeeping violations—failure to maintain required documentation such as age verification. On the other hand, hazardous occupation violations remained similar across both types of states. Analysis of employment certificate forms from all 38 states with mandates reveals why: While 100% mention age requirements and 60% mention work hours restrictions, most forms do not enumerate the specific hazardous occupations prohibited under federal law.

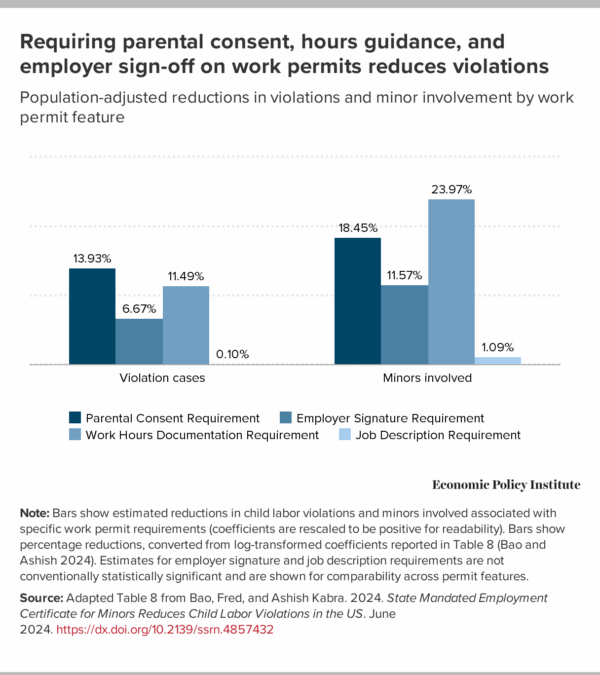

Figure A Parental consent and hour limits provide strongest protection

Parental consent and hour limits provide strongest protection

The researchers also examined which features make permits most effective. Figure B highlights the findings. Examining employment certificate forms from 37 of the 38 states that require them (Mississippi’s form was not publicly available), researchers found that parental consent requirements had the strongest protective effect, reducing violations by 13.9% and case severity by 38.7% (measured by civil penalties assessed). Work hours documentation—in which the certificate must record the minor’s planned work schedule (typically completed by employers, though responsibilities vary by state)—also proved effective, reducing the number of minors involved in violations by 24.0%. In contrast, more passive requirements, such as employer signatures and job description requirements, showed lesser independent effects. This suggests that active oversight mechanisms, particularly parental involvement and explicit requirements to record work schedules to show compliance with legal guidelines on hours of work, drive the protective benefits. That these two features are particularly impactful provides further evidence that requiring employer documentation on work permits and verifying parental consent make work permits effective.

Figure B Work permits prevent violations. State lawmakers should strengthen, not eliminate them.

Work permits prevent violations. State lawmakers should strengthen, not eliminate them.

Understanding how work permits prevent violations points to ways for states to further increase their effectiveness. The researchers identified four best practices lawmakers should consider:

- Strengthen parental consent requirements: Youth work permit applications should require parental signature and include a process for parents to revoke their consent in the future.

- Strengthen requirements to outline the specific duties of the potential job: Youth work permit applications should require employers to document specific duties of the potential job and include the minor’s planned work schedule.

- Include information about hazardous occupation restrictions on permit forms: Youth work permit applications should include a list of prohibited jobs for minors under state and federal law and affirm the employer’s commitment not to employ a minor for hazardous tasks and occupations.

- Clearly state hour limits: Youth work permit applications should include permitted daily and weekly hours and prohibitions on overnight work under both state and federal law. These forms should also clearly state that, where there are discrepancies between state and federal law, the more protective law applies.

These new insights into how youth work permits function reinforce the researchers’ original conclusion: Youth work permits are a proven method for reducing child labor violations. And they show that the permitting process can be a highly effective vehicle for educating employers, teen workers, and parents about legal rights and protections. States with existing work permit systems can strengthen them to enhance their protective effects—as Illinois, Michigan, and Washington have done—and states that do not have work permit requirements should take immediate steps to implement or reinstate them.

1. Throughout this report, the terms “work permits” and “employment certificates” are used interchangeably. Age certificates are distinct and more limited; they typically verify age but do not include the same safeguards.

Trump Accounts distract us from real solutions that lean on the functional power of wealth, a strong labor market and welfare state

Trump Accounts distract us from real solutions that lean on the functional power of wealth, a strong labor market and welfare state

Recent comments