The Savings and Loans Crisis of the 1980's was one of the biggest financial crises in US history. The insurer for savings and loans, the FSLIC became insolvent and was abolished in 1989. A new institution, the Resolution Trust Corporation (RTC) was established to liquidate failed financial institutions. Federal insurance of S&L deposits was transferred to the FDIC in 1989.

One contemporary account described the scope of the financial meltdown as follows:

The failure rate of FSLIC insured savings and loan associations (S&Ls) in the United States during recent years has assumed unprecedented proportions. For the period from 1934 through 1941, a total of 33 F.S.L.I.C. insured S&Ls failed. Over the period from 1942 through 1962, a total of 15 FSLIC insured S&Ls failed. The number of failed so-insured S&Ls rose to 82 for the period from 1963 through 1979. However, since 1980, the annual number of failed FSLIC insured S&Ls has reached unprecedented levels. Indeed, ... over the period 1980 through 1989, a total of 525 FSLIC insured insolvent S&Ls failed

The FSLIC, like the FDIC, required member banks to pay a premium, equal to 1/12 of 1% of deposits. By 1985, that fund was underfunded, having only $4.55 billion and by 1986, had a negative fund reserve of -$6.3 billion.

The Savings & Loan crisis, and the insolvency of the FSLIC have been extensively studied. I'll provide some links in the course of this diary to some thorough studies, but for our purposes we can note that it is a textbook case of how deregulation without oversight is a disaster waiting to happen when it comes to the banking industry, an ominous sign indeed.

The FDIC itself has put together several excellent presentaions of the crisis, which I'll make extensive use of here. While the crisis began in the early 1980s, the stage was set by several prior decisions:

1. The FSLIC (like the FDIC even now) does not vary insurance premiums by the risk undertaken by member banks. As one commentator has pointed out:

Federal deposit insurance... provided by the federal government tolerated the unsound financial structure of S&Ls for years. ... Federal deposit insurance is unsound primarily because it charges every S&L the same flat-rate premium for every dollar of deposits, thus ignoring the riskiness of individual S&Ls. In effect, the drunk drivers of the S&L world pay no more for their deposit insurance than do their sober siblings.

2. In 1967, the State of Texas approved a major liberalization of S&L powers, allowing property development loans of up to 50% of net worth. Since S&Ls operating under state charters were allowed to obtain FSLIC, this meant that states with the most reckless standards could still qualifiy on the same basis for Federal insurance. Later, 50% of all losses were to come from Texas S&Ls. This was compounded in 1982, when, In response to the massive defections of state chartered S&Ls to the federal system, California, and then Texas and Florida allowed S&Ls to invest 100% of deposits in any kind of venture.

3. Savings and Loans were specialized banks that used low-interest, but Federally-insured, deposits in savings accounts to fund mortgages.S&Ls, like mutual savings banks, invest short term deposits and loan long-term in mortgages. This created a "maturity mismatch" which became acute during the severe inflation of the late 1970s and early 1980s. The same commentator as cited above, noted that "between June 1979 and March 1980 short-term interest rates rose by over six percentage points, from 9.06 percent to 15.2 percent. In 1981 and 1982 combined, the S&L industry collectively reported almost $9 billion in losses. Worse, in mid-1982 all S&Ls combined had a negative net worth, valuing their mortgages on a market-value basis, of $100 billion, an amount equal to 15 percent of the industry's liabilities."

Against this backdrop, both the Carter and Reagan Administrations extensively deregulated the industry:

regulators in the early 1980s lacked the political, financial or human resources to close large numbers of institutions. Rigorous enforcement would have meant paying out much more money to insured depositors than was held in the industry-funded FSLIC insurance fund. It would also have meant working with literally hundreds of insolvent institutions, and overcoming numerous political obstacles at a federal and state level to radical S&L industry reform.

Instead, between 1980 and 1982, regulators, industry lobbyists and legislators put together various legislative and regulatory mechanisms to postpone the threatened insolvency of the sector in the hope that interest rates would quieten down and S&Ls would be able to engineer themselves back into profitability.

..., the sum effect of these mechanisms was to loosen S&L capital restrictions, while offering S&Ls new freedom to extend their activities into potentially lucrative (and therefore risky) areas.

What this incomplete and bungled deregulation allowed is breathtaking, and serves as a stark warning for our own time:

Congress and the regulators granted S&Ls the power to ... make real estate loans without regard to the geographical location of the loan, and permitted them to lend up to 40 percent of their assets in commercial real estate loans... . However, the 1980 and 1982 legislation did not change how premiums were set for federal deposit insurance. Riskier S&Ls still were not charged higher rates for deposit insurance than their prudent siblings. As a result deregulation encouraged increased risk taking by S&Ls.

Capital standards were debased in the early eighties in an extremely unwise attempt to hide the economic insolvency of many S&Ls. ... [A]ccounting gimmicks permitted S&Ls to operate with less and less capital. Therefore, just as S&Ls, encouraged by deregulation, took on more risk, they had a smaller capital cushion to fall back on.

Inept supervision and the permissive attitude of the FHLBB during the eighties allowed badly managed and insolvent S&Ls to continue operating.... These powers encouraged unscrupulous real estate developers and others who were unfamiliar with the banking business to acquire and then rapidly grow their S&Ls into insolvency.

The FDIC chronology shows that as the S&Ls undertook riskier loans and in some case became criminal operations, the regulator was drained of resources by an ideologically blinded Administration:

November, 1980--Federal Home Loan Bank Board reduces net worth requirement for insured S&Ls from 5 to 4 percent of total deposits. Bank Board also removes limits on the amounts of brokered deposits an S&L can hold.

September, 1981--Federal Home Loan Bank Board permits troubled S&Ls to issue "income capital certificates" that are purchased by FSLIC and included as capital. Rather than showing that an institution is insolvent, the certificates make it appear solvent.

January, 1982--Federal Home Loan Bank Board reduces net worth requirement for insured S&Ls from 4 to 3 percent of total deposits.

April, 1982--Bank Board eliminates restrictions on minimum numbers of S&L stock holders....Bank Board's new ownership regulation would allow a single owner. Purchases of S&Ls were made easier by allowing buyers to put up land and other real estate, as opposed to cash.

1982-1985 Reductions in the Bank Board's regulatory and supervisory staff... . The average examiner has only two years on the job. ... industry growth increases. Industry assets increase by 56% between 1982 and 1985. 40 Texas S&Ls triple in size between 1982 and 1986; many of them grow by 100% each year. California S&Ls follow a similar pattern

1983--....9% of all S&Ls (representing 10% of industry assets) are insolvent by GAAP standards.

But as difficult as the situation may have appeared by the end of 1983,

Delayed closure of insolvent S&Ls greatly compounded FSLIC's losses by postponing the burial of already dead S&Ls.... Congress chose to put off the eventual day of reckoning, which only compounded the problem

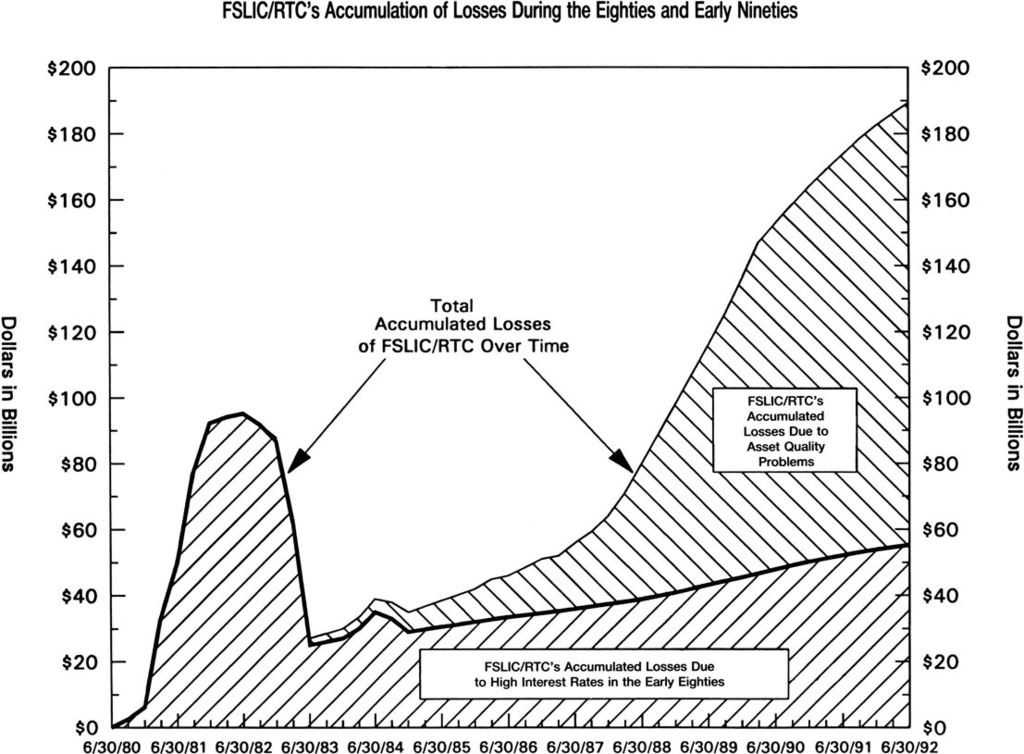

as is demonstrably shown in the below graph of accumulated losses to the FSLIC and RTC:

The FSLIC's "claimed reserves totaled only $4.6 billion at the end of 1985. In contrast, the unrecognized claims against the fund totaled over $29 billion."

According to the previously cited FDIC study:

As a consequence of all these factors,... [t]he result ... was the failure of hundreds of thrift institutions and the insolvency [as declared by the GAO] by year-end 1986 of the FSLIC, the federal insurer for the thrift industry. As of year-end 1986, 441 thrifts with $113 billion in assets were book insolvent, and another 533 thrifts, with $453 billion in assets, had tangible capital of no more than 2 percent of total assets. These 974 thrifts held 47 percent of industry assets.

The financial disaster continued to escalate even after Congress finally stepped in, why by the end of 1989 saw the compounding of losses as insolvent institutions were allowed to remain open and grow, allowing ever increasing losses to accumulate. In other words, the "zombie" S&L's kept remained open, making bad loans, and the losses kept mounting.

Ultimately, the number of Federally insured Thrifts (S&L) dropped 50% or from 3,234 in 1986 to 1,645 by the beginning of 1996. 32.25% of all thrifts failed.The end result was the biggest bailout ever foisted on the US taxpayer until now:

For some years the final bill for the S&L crisis remained uncertain. However, we know now that, setting aside ongoing legal action, the thrift crisis cost an extraordinary $153 billion - easily the most expensive financial sector crisis the world has ever seen. Of this, the US taxpayer paid out $124 billion while the thrift industry itself paid $29 billion.

In the final installment: Comparing today's financial crisis

(i would like to thank Rob Oak for assistance in researching and editing this series).

Comments

more than deregulation

There was a tax law which allowed anyone to deduct losses and depreciation on rental property, i.e. a tax shelter. That led to everyone and their brother buying up rental property for a tax shelter, putting together limited partnerships and having passive losses.

Then, due to inflation, interest rates went through the roof and S&Ls were sitting on loans with low interest rates, so their value on the secondary markets plummeted.

They also couldn't do money markets, which caused depositors to move their money out to places for higher returns.

So, you've got this massive real estate boom going on because folks want that tax shelter and on top of it, they are buying up anything, because it's not the actual real estate value they are looking at, it's the tax shelter. So, you've got this market for residential, commercial real estate with interest rates going up to 19%!

Then, even worse, in 1986, Congress abruptly changed this tax shelter, catching tons of high income middle class people in the pants with rental property they really couldn't afford and massive taxes owed. They didn't do a graduated enough or assuredly not a high enough AGI considering gross income required, this was a blunt change, too blunt.

So, with that change, well, real estate was heavily overbuilt and add to that the interest rates were absurdly high and didn't make much sense unless one was getting a tax shelter out of it.

Oops, big crash in Real Estate. Guess who is left holding the bag on foreclosed properties? S&Ls.

tax code revision, 1986

How badly did it catch your typical high income middle class individual? Bad! New York Times piece breaking down how an individual couldn't write off passive losses and because their income was limited, well, they plain got stuck.

So, one can point a finger at the Reagan administration and at Congress for suddenly changing the tax code and assuredly the ones they did not watch out for where those higher income middle class professionals hunting for tax shelters they could afford. They were the ones never bailed out.